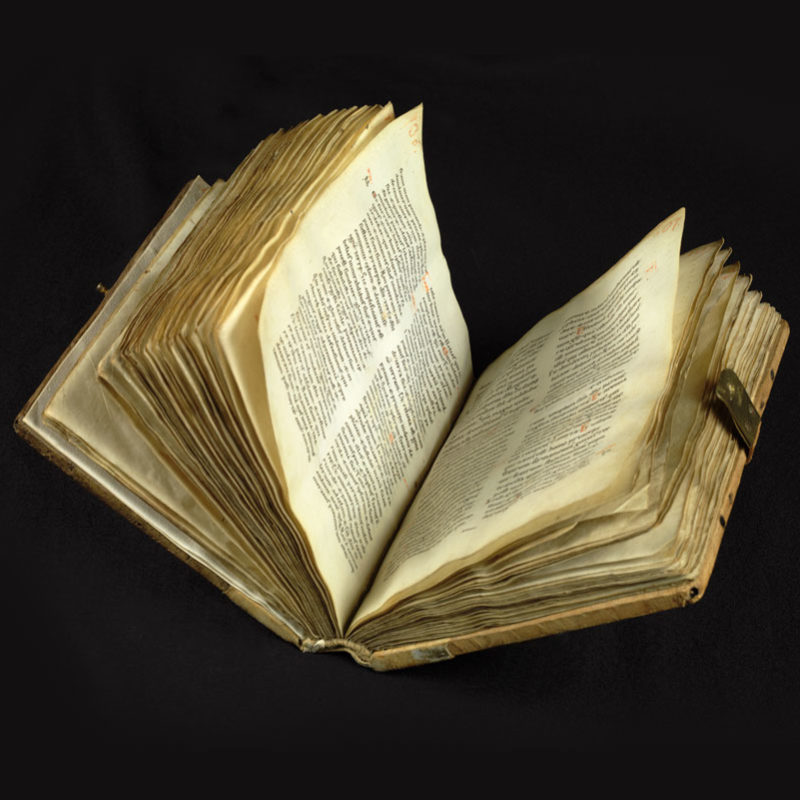

The Abbey Library of St. Gall in Switzerland is home to approximately 160,000 volumes of literary and historical manuscripts dating back to the eighth century — all of which are written by hand, on parchment, in languages rarely spoken in modern times.

To preserve these historical accounts of humanity, such texts, numbering in the millions, have been kept safely stored away in libraries and monasteries all over the world. A significant portion of these collections are available to the general public through digital imagery, but experts say there is an extraordinary amount of material that has never been read — a treasure trove of insight into the world’s history hidden within.

Now, researchers at the University of Notre Dame are developing an artificial neural network to read complex ancient handwriting based on human perception to improve capabilities of deep learning transcription.

“We’re dealing with historical documents written in styles that have long fallen out of fashion, going back many centuries, and in languages like Latin, which are rarely ever used anymore,” said Walter Scheirer, the Dennis O. Doughty Collegiate Associate Professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at Notre Dame.

“You can get beautiful photos of these materials, but what we’ve set out to do is automate transcription in a way that mimics the perception of the page through the eyes of the expert reader and provides a quick, searchable reading of the text.”

In research published in the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers journal Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, Scheirer outlines how his team combined traditional methods of machine learning with visual psychophysics — a method of measuring the connections between physical stimuli and mental phenomena, such as the amount of time it takes for an expert reader to recognize a specific character, gauge the quality of the handwriting or identify the use of certain abbreviations.

Scheirer’s team studied digitized Latin manuscripts that were written by scribes in the Cloister of St. Gall in the ninth century. Readers entered their manual transcriptions into a specially designed software interface. The team then measured reaction times during transcription for an understanding of which words, characters and passages were easy or difficult. Scheirer explained that including that kind of data created a network more consistent with human behavior, reduced errors and provided a more accurate, more realistic reading of the text.

“It’s a strategy not typically used in machine learning,” Scheirer said. “We’re labeling the data through these psychophysical measurements, which comes directly from psychological studies of perception — by taking behavioral measurements. We then inform the network of common difficulties in the perception of these characters and can make corrections based on those measurements.”

Using deep learning to transcribe ancient texts is something of great interest to scholars in the humanities.

“There’s a difference between just taking the photos and reading them, and having a program to provide a searchable reading,” said Hildegund Müller, associate professor in the Department of Classics at Notre Dame. “If you consider the texts used in this study — ninth-century manuscripts — that’s an early stage of the Middle Ages. It’s a long time before the printing press. That’s a time when an enormous amount of manuscripts was produced. There is all sorts of information hidden in these manuscripts — unidentified texts that nobody has seen before.”

Scheirer said challenges remain. His team is working on improving accuracy of transcriptions, especially in the case of damaged or incomplete documents, as well as how to account for illustrations or other aspects of a page that could be confusing to the network.

However, the team was able to adjust the program to transcribe Ethiopian texts, adapting it to a language with a completely different set of characters — a first step toward developing a program with the capability to transcribe and translate information for users.

“In the literary field, it could be really helpful. Every good literary work is surrounded by a vast amount of historical documents, but where it’s really going to be useful is in historical archival research,” said Müller.

“There is a great need to advance the digital humanities. When you talk about the Middle Ages and early modern times, if you want to understand the details and consequences of historical events, you have to look through the written material, and these texts are the only thing we have. The problem may be even greater outside the Western world. Think of languages that are disappearing in cultures that are under threat. We must first of all preserve these works, make them accessible and, at some point, incorporate translations to make them a part of cultural processes that are still underway — and we are racing against time.”

— Jessica Sieff, Notre Dame Media Relations